The U.S. is facing a new wave of Covid-19 outbreaks straining hospitals, workers, businesses, and schools.

In this, the country is not alone: Wealthy nations across Europe are facing a major surge in new infections too, as is Canada. But unlike their economic peers, elected leaders in the U.S. have left citizens to face the current crisis without any additional financial cushion from their government.

In the United Kingdom, the conservative government led by Prime Minister Boris Johnson has extended relief to workers that had been set to expire — a lifeline for millions contending with new lockdowns across the country. In Germany, officials approved more funding to compensate businesses affected by health restrictions. And in Canada, a new budget plan lays out more aid to businesses in hard-hit sectors to complement ongoing subsidies for workers, including $2,000 a month for those who have lost jobs or income due to the pandemic.

“Most of what they put into place in March and April has now been extended and beefed up,” said Armine Yalnizyan, an economist at the Atkinson Foundation tracking Canada’s response.

The U.S. has gone the opposite direction, letting benefits for workers and businesses expire with no agreement yet in Washington on a new aid package.

A weekly benefit of $600 for people who lost their jobs or couldn’t work in the pandemic ended in July with no legislative replacement, and funding to keep small businesses afloat is tapped out as well. An extension of state unemployment benefits is set to end after this month as well, along with eviction protections for renters, a paid leave provision, and a freeze on student loan payments.

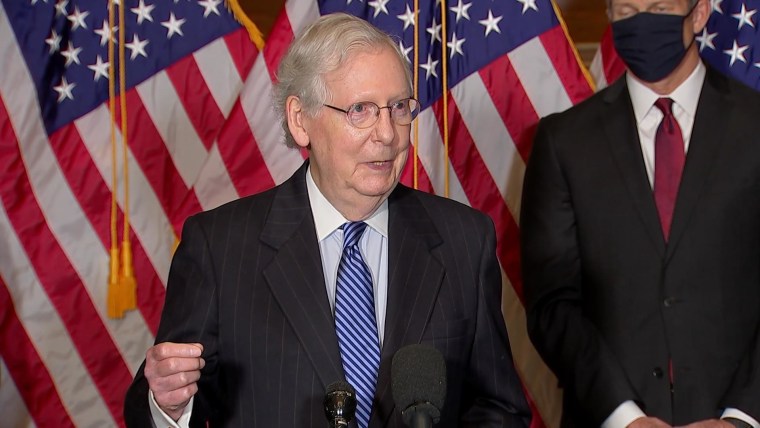

The White House and Congress have been locked in debate for months on new relief, with Democratic leaders recently embracing a bipartisan bill to provide about $900 billion in aid and President Trump and Republican leaders initially backing a smaller figure. While talks have picked up steam in recent days, there’s still no deal.

The lack of assistance from Washington has taken on additional urgency in recent weeks. Job growth abruptly slowed in November and 10 million fewer people are working than when the pandemic hit last spring.

It’s also made it more difficult for states to follow guidance from Dr. Anthony Fauci and other public health experts, who recommend shutting down high-risk businesses like bars and indoor restaurants in order to curb outbreaks and make it safer to keep schools open.

Without additional relief, state and local governments face no-win decisions between imposing recommended health rules and bankrupting local businesses.

“I know multiple industries have been lobbying governors to stay open because closing means a huge loss of income to business owners and employees, even if it would be the best thing to do from a public health perspective,” said Tara C. Smith, an epidemiologist at Kent State University. “Federal relief would help to alleviate some of these concerns.”

European countries have imposed stricter health measures to curb the latest spike in infections, including widespread stay-at-home orders. While such measures can be politically divisive there, as they are in the U.S., cases have begun to decline across the European Union overall. But in the U.S, infections, hospitalizations, and deaths are still hitting new highs amid a jumble of rules that vary from state to state and city to city.

The aid provided by the government varies by country in Europe, but economists say there are some common features. In many places, relief was designed as a subsidy for businesses to keep workers on payroll while paying a percentage of their wages rather than moving them to unemployment.

Some countries have benefited by having systems in place that were created to respond to prior recessions. Germany’s “Kurzarbeit” program, for example, which pays a portion of wages to encourage companies to keep workers on reduced hours rather than lay them off, was considered a success story after the 2008 financial crisis and proved a model for other countries.

“These furlough schemes have been very effective so far at limiting fallout in jobs,” Ken Wattret, Chief European Economist at IHS Markit, said. “We’ve had one in the UK, the French, Spanish and Italian governments have variations. They are all different in specifics, but the general point of them is the same.”

The U.S. lacks the technical infrastructure right now to follow Europe’s model. But earlier in the pandemic, the scale of aid kept pace with other advanced economies, bucking stereotypes about America’s reluctance to finance a social safety net comparable to Europe. By some measures, U.S. relief efforts were even larger in scope and more generous.

The $2.2 trillion CARES Act’s core benefit — a $600 weekly check for anyone unable to work due to the pandemic on top of state unemployment benefits — often amounted to more than workers had been making at their jobs. That meant the aid went further than other countries where benefits were capped as a percentage of prior wages.

The CARES Act also authorized stimulus checks of $1,200 for adults and $500 for children to most households. To help support businesses, it provided hundreds of billions of dollars in loans through the Paycheck Protection Program, which could be converted to grants if owners spent them on keeping workers on payroll.

Relief provided by the CARES act had an enormous impact. Even after the economy collapsed last spring, poverty rates initially held steady, according to a Columbia University study in June. Many Americans were even able to build up a pool of savings to help tide them through the pandemic.

Most of the CARES act funding was temporary, aimed at helping workers through what lawmakers hoped would be a relatively short period needed to get the virus under control. Instead, benefits began to expire as the pandemic worsened.

“If the overly optimistic forecasts had been right and we shut down in March and were back in summer, the approach wouldn’t have been too bad,” Claudia Sahm, a former Federal Reserve economist, said.

Unlike some comparable economies, America’s aid was a one-time package, rather than an automatic benefit that continued so long as economic conditions remained dire. Instead, a mix of election year politics, skepticism from Republicans about the need for more spending, and shifting positions by President Trump made it difficult to find consensus on new aid.

The $600 jobless benefit cut off at the end of July. It was patched over with a $300 replacement through a White House executive order for six weeks, but with that gone, income dropped by more than half for many who were still unemployed. The Paycheck Protection Program also ended, leaving businesses in the lurch during new outbreaks that are dragging down revenues in the holiday season and forcing new restrictions on indoor activities.

“All of this is running out before the vaccine helps us get the pandemic under control,” Sahm said. “A light at the end of the tunnel does not pay the bills.”

In Europe and Canada, by contrast, emergency aid was either passed without a fixed end date or easily renewed, even as politicians still argued over the scope of health restrictions and how to address long-term debt once the crisis passed.

“The key is people are still covered by these schemes and will be right through the winter,” said Ian Shepherdson, chief economist at research firm Pantheon Macroeconomics. “None of them have been withdrawn.”

Now, experts fear the lapse in aid is dragging down the most vulnerable Americans and shuttering small businesses just as spiking Covid-19 infections put their health at risk. When the same Columbia University researchers reported back in October, they found 8 million Americans had fallen into poverty. About 1 in 6 households with children report not having enough food, according to the Census Bureau, and the numbers appear to be worsening.

While the economy is expected to bounce back once a vaccine is widely distributed, the misery inflicted before then could be severe. Lost businesses and permanent layoffs could potentially prolong the recovery.

“The question is should a rich country allow thousands of businesses to fail just because the government couldn’t get their act together,” Shepherdson said. “It’s a moral imperative as much as a macroeconomic imperative.”

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com