Can 2020 please be the year that finally kills New Year’s resolutions?

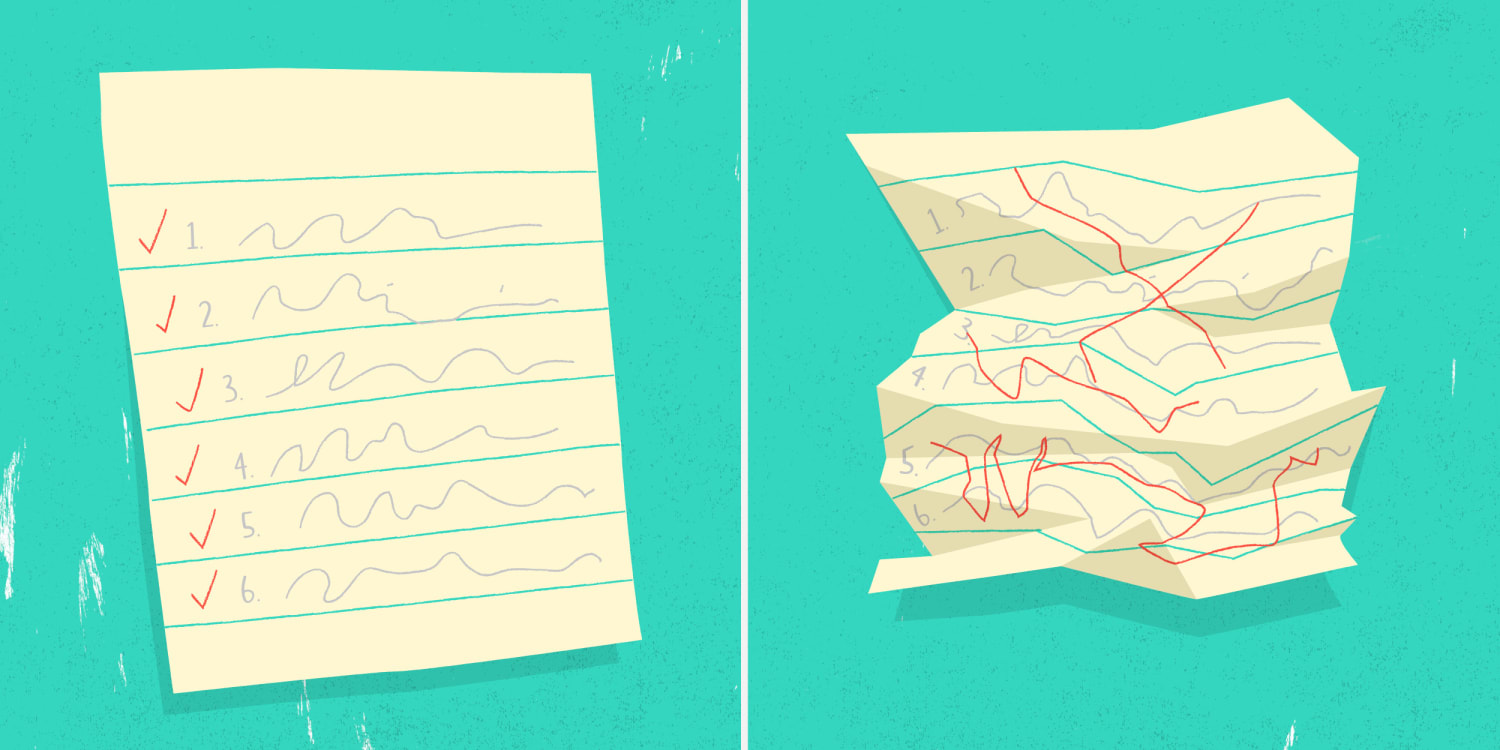

This yearly ritual is not just a collective waste of time — it actively sets most of us up for failure.

By Natasha Noman

We’ve all been there: Come Jan. 1, we endeavor to embark on a host of life-changing behaviors in the form of New Year’s resolutions — from eating less to exercising more, from drinking less to volunteering more. But while it’s perhaps well-meaning, I’ve come to dread this yearly ritual. And a number of studies back me up.

It’s not exactly breaking news. A longitudinal study over two years more than three decades ago found that 77 percent of people kept their resolutions for one whopping week. More recently, and specific to exercise-related resolutions, “quitter’s day” — or the grim date when these dramatic self-promises are abandoned — typically falls between the second and third weeks of January (far more promising than the longitudinal study’s results), according to data gleaned from hundreds of millions of entries in the fitness app Strava over the past few years.

New Year’s resolutions are not just a waste of time in terms of how few people actually see them through; I would also argue that they actively set most of us up for failure and are, therefore, more likely to discourage us from meeting our goals.

Part of the issue stems from how we think about making life changes. It seems both the scale of change and the source of motivation for New Year’s resolutions are problematic.

Changing our behavior is a difficult and complex task, and it’s most often successful when it’s done in small, quantifiable steps (e.g., “I vow to eat one raw vegetable per day” or “I’ll exercise an hour per week”). One of the prevailing theories about changing behaviors is the Transtheoretical Model of Change, which, according to the American Psychological Association, includes the five stages of “precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance.” This requires considerable investment in both time and emotion. It is far more involved than the bifurcated approach to resolutions: deciding to make the change and then making it. In short, changing behavior in the long run is a huge commitment.

And all too often, the motivation for our resolutions, like losing weight or quitting vaping, comes from a place of fear rather than hope — a problem I believe extends into other areas of our lives.

“One potential roadblock: too often we’re motivated by negatives such as guilt, fear, or regret,” according to a paper about New Year’s resolutions published by Harvard Medical School in 2012. “Experts agree that long-lasting change is most likely when it’s self-motivated and rooted in positive thinking.” (Though, it should be noted, while the paper acknowledges the difficulty of following through on resolutions, it doesn’t openly discourage them.) The paper also notes that the five psychological stages of change, which can be thought of as building blocks, aren’t to be rushed through, lest you create a weak foundation in behavior and relapse.

And then there’s the issue of timing. While it has symbolic significance, practically speaking Jan. 1 is an arbitrary time to try to overhaul our lives. Many people will have just spent the previous day partying, perhaps waking up sluggish or even ill. And I literally can’t think of a less motivating time than the dead of winter after the holidays are all done. January is supposed to be one of the most depressing times of the year, not least because of seasonal affective disorder, or SAD, is a kind of depression likely to be precipitated by less exposure to sunlight, which affects an estimated 10 million Americans.

But even if you don’t officially suffer from SAD, January just tends to be kind of, well, sad.

“There is generally more sadness in the winter time and January is not uncommon at all for overall more sadness among folks,” Dr. Ravi Shah, a psychiatrist at Columbia University’s Irving Medical Center, told CNN. Add that we’re going through a pandemic, which is essentially a societywide trauma, and the whole prospect feels doomed. These are not, on the whole, the conditions that will set us up for success.

For all these reasons, I think it’s time to stop forcing this collective aspirational spasm. As I get older, I’ve become more aware of when I’m setting myself up for failure — and I try harder to avoid it.

This isn’t to say that change is impossible. It’s good to try to motivate yourself to correct or ameliorate unhealthy behavior. I’ve adopted a three-pronged framework that works for me: choose a motivating time of the year to institute changes (I find late spring and summer very energizing), attempt to positively frame the motivation for changing my behavior and try to be really rigorous about making any changes incrementally. In addition, I try to be kind to myself if I have little relapses here and there (i.e., don’t throw the baby out with bathwater and give up entirely).

It should be emphasized that there are no hard and fast rules — which is kind of my whole point. Implementing changes in behavior is incredibly specific to the individual (we all have different barriers to making change and triggers for relapsing, for example), and it tends to require trial and error.

If you want to change, to try to make a positive life change, I will gladly be your hype woman (I’m serious!). But just remember that self-improvement journeys begun on Jan. 1 are, statistically speaking, very likely to fail. Sure, the start of a new year — and saying farewell to the dumpster fire that has been 2020 — feels like a good time to hit the restart button. But perhaps, instead, you can use this period for self-evaluation, embarking on the first three stages of the Transtheoretical Model of Change (precontemplation, contemplation and preparation) in anticipation of instituting lasting adjustments once winter’s fog of gloom ascends. That will give you time to internalize the need for whatever change you want to introduce in your life, as well as make a comprehensive plan of how you’ll achieve it.

This year has been hard enough. Don’t continue the disappointment by buying into the fallacy of New Year’s resolutions.

Natasha Noman is a journalist who has worked as a writer, producer and presenter for publications such as Mic, Bloomberg and Brut America, with a focus on the Middle East and South Asia. She is working toward a master of philosophy degree in South Asian studies at the University of Oxford.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com