Last week, Russian President Vladimir Putin instructed his cabinet to launch a new investment cycle “to ensure economic growth rates above the world level.” Yet just a few weeks earlier, he recommended the legislature pass laws to protect investments in Russian industry—specifically highlighting the need to protect Russian data. (As with all of Putin’s “recommendations,” it came with a deadline attached: April 30.)

Russia is not the only country scrutinizing foreign investments in its domestic tech while simultaneously pushing for economic growth. The United States, Israel, China, and other countries are seeking to build better screens.

WIRED OPINION

ABOUT

Justin Sherman (@jshermcyber) is an Op-ed Contributor at WIRED and a Fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Cyber Statecraft Initiative.

State inspection of foreign investments at home isn’t novel. Probing NGOs and mandating registration of foreign lobbyists are just two decades-old examples. What’s different today is that countries are accelerating and expanding these powers where they already exist, or freshly architecting them altogether. It’s a way for governments to address two things: perceived foreign influence over their domestic technology spheres, and perceived risks of foreign governments using investments and acquisitions to access sensitive data.

Let’s start in the States. Acronyms are the lingua franca of government bureaucracy, and the US’ process for vetting foreign money poured into American firms is no exception: CFIUS, or the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States.

Established in 1975 through a Ford administration Executive Order, CFIUS is composed of representatives from State, Treasury, Defense, and numerous other agencies. The whole point is to balance myriad interests—broadly, economic and security goals. Of all entities within the executive brand, it has primary responsibility for watching foreign investment in the States. Its recommendations can lead to blocking covered transactions that threaten US national security—and even undoing those already completed.

CFIUS’ members and authorities have shifted and expanded over time, but the notable expansion—and use—of its powers during the Trump administration typifies the growing scrutiny applied to overseas money seen around the globe, specifically in tech. The administration has blocked deals for everything from semiconductors to flight services. In 2018, a Chinese firm’s acquisition of an American payment company imploded after CFIUS refused to clear it.

Lately, CFIUS has zeroed on deals centered on data, like when it informed Chinese company Beijing Kunlan Tech it had to sell the dating app Grindr. Information on sexual preferences and activity, the logic went, is too sensitive to risk falling into the Chinese government’s hands. And while the last time CFIUS publicly released investigation statistics was 2015, those numbers and recent press reports indicate a growing and heavy focus on Chinese investments in US tech.

Israel is now trotting a similar path. As Chinese money in Silicon Valley caught more attention in Washington, a “honeymoon” period resulted for Israel: The country was glad to source new investors as Chinese actors happily pumped money into the Israeli tech sector. Pressure from the Trump administration ended this brief vacation.

In late October 2019, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s office issued a statement on the planned creation of what is essentially an Israeli CFIUS. Its aim: “finding the appropriate balance” between economic prosperity and national security vis-à-vis investments. Also like CFIUS, the panel will be composed of finance and defense officials and will consult other stakeholders across foreign policy and intelligence. Nobody explicitly called out China in the announcement, but for anyone watching the Trump administration’s view of Beijing, the primary target of this change is hardly in doubt.

For his part, Putin has long been suspicious of Western technology influences within Russia, as have his close advisers. Foreign investments in Russian media companies, for instance, are already limited. Putin’s latest recommendations follow a series of moves to shrink perceived foreign threats specifically to Russia’s tech sector. Yandex—the internet company with a global presence unusual for many Russian tech firms—is a relevant case study.

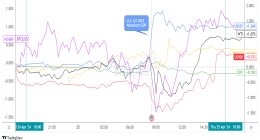

Tactfully managing its international business presence against the Kremlin’s domestic wishes has been a years-long and continuous project for Yandex, as well-documented in books like The Red Web. The latest step in this dance came last fall. After the media reported that Kremlin officials welcomed further limits on foreign investments in tech companies, Yandex’s share prices sharply fell. Further discussion of possible legislation aimed at companies who “collect information on [Russian] users” increased Yandex’s uncertainty.