April 14, 2020 15+ min read

This story appears in the April 2020 issue of Entrepreneur. Subscribe »

Ben Weprin, CEO of the company behind Graduate Hotels, is standing tall on the unfinished rooftop of the building he has spent four years willing into existence. Once complete, this will be the only hotel on Roosevelt Island, a two-mile crust of grass and concrete that runs alongside Manhattan’s eastern shore. “Every time I’m up here, I still can’t believe this is happening,” Weprin says. “It’s unreal.”

Many New Yorkers might say the same. For most of them, Roosevelt Island is little more than a curious patch of land they cross over while driving from Manhattan to Queens. A hotel there? Why? As Weprin stands on the roof, he seems to revel in the counterintuitiveness of it. Today’s sky is wet and heavy, and in the distance, the Chrysler Building appears as a cold silhouette against a gray background. “Over there is the old insane asylum,” he says, gesturing to what this place was once most famous for. “That’s where they’ll put me, eventually.”

But Weprin doesn’t appear to be insane. Instead, he’s an entrepreneur with a keen eye for opportunity, and he’s building here on Roosevelt Island for a specific reason: Cornell University has opened a new campus called Cornell Tech. That means Weprin will do what he does best. He’ll build the hotel that every Cornell student will want to hang out at, and every visitor will want to stay at — not just because it’s there, but because it feels like theirs.

Related: To Beat the Competition, Become the Most Convenient Option for Customers

At 41, Weprin could pass for a graduate student. He is certainly dressed the part — worn leather boots, Army-style camo socks, a plaid button-up emerging from the navy-blue collar of his quarter-zip mock-neck sweater. As his brainchild, Graduate Hotels is a chain that romanticizes the college experience. It allows alumni to relive their past and recruits to see their future. Using yearbook photos, student ID key cards, and jars full of No. 2 pencils, the hotel aims to re-create the feeling of limitless future a student experiences while rooting at the homecoming game or partnering up with a study buddy whose pheromones imply more than academics.

“We’re focused less on demographics than on psychographics,” says Weprin later on, over a cup of coffee. “It’s all about that state of mind you have when you’re in college.”

If it sounds like a small idea — well, it’s not. Since its launch in 2014, Graduate Hotels has grown to 22 properties, with three more scheduled to open this month, followed by five more throughout 2020. All of them sit either on or adjacent to the campus they serve. Initially, the brand took aim at secondary and tertiary markets, where campus life dominated the local economy. “I thought this would be a cute little seven-to-10-hotel portfolio in a few college towns,” says David Rochefort, Graduate’s president. “We’d have a little fun and sell it off, then we’d move on to the next thing.”

But that’s not what happened. The first 10 hotel openings came and went, and the brand kept growing. This year, in addition to New York City, Graduate will open in big markets such as Tucson and Dallas. The question is: How big can a niche idea really get?

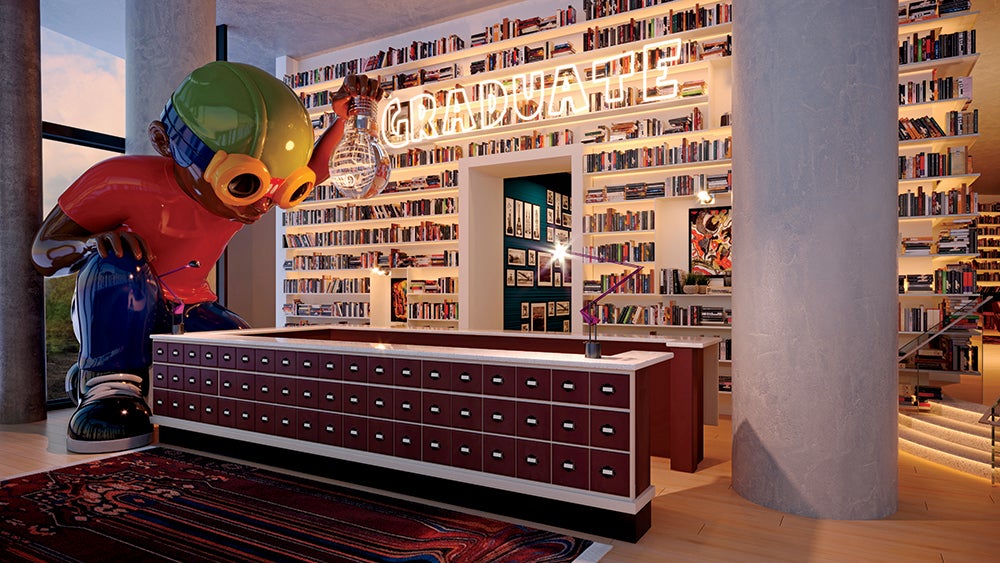

A rendering of the front desk at the soon-to-open Graduate Hotel on New York’s Roosevelt Island

Image Credit: Courtesy of Graduate Hotels

As a teenage shoe salesman in Dayton, Weprin learned how to close deals. He attended business school at the University of Tennessee, began managing hospitality assets out of college, and then formed AJ Capital Partners — the AJ is for “adventurous journeys” — to buy his first hotel in the midst of the 2008 financial crisis.

“Literally, I was out of my mind,” he says. Maybe so, maybe not — but he was also now the proud owner of the Hotel Saint-Barth Isle de France, in St. Barts. It actually did well. Soon, Weprin began adding to his portfolio properties, mostly around his home in Chicago.

One of the early acquisitions was a shuttered Days Inn near his apartment in Lincoln Park. People advised him not to buy it. They said it was too far from downtown and he’d never get weekday guests. There was a reason it closed, right? But Weprin saw the nearby zoo and DuPaul University as untapped traffic drivers. And Frank Baum had lived nearby while writing The Wizard of Oz. Surely those hyperlocal factoids could lure guests away from more traditional business centers.

In 2012, the old Days Inn reopened as Hotel Lincoln. Its success proved out Weprin’s instinct, but more important, it planted the seed of what would eventually become Graduate Hotels.

Related: 8 Things to Consider Before You Open a Second Location

While AJ Capital was building its name in Chicago, university towns were thriving. During the 20-year stretch between 1993 and 2013, four-year college enrollment increased by 43 percent, and private developers stepped in to meet the increased demand for student housing. AJ Capital wondered: Could it do the same thing for hotels?

Having launched in the tumult of a recession, AJ Capital was acutely aware that shifting market forces can wreck a portfolio. But college towns could serve as a life raft in an economic downturn. “In ’08, admissions actually increased,” says Rochefort. “People were going back to school for MBAs and grad programs.”

Once the idea surfaced, the team moved fast. They created a target list of 50 university markets, assigned each one a grade (based on size, attainable properties, and so on), and began making acquisitions. “We wanted to have the first-mover advantage,” says Weprin. “And we wanted to scale quickly to distance ourselves from the competition.”

In October 2014, AJ Capital opened two Graduate Hotels, in Tempe, Ariz., and Athens, Ga. The next year, it opened three: Madison, Wis.; Charlottesville, Va.; and Oxford, Miss. “We were acquiring existing hotels that we could convert quickly,” says Rochefort. “We basically launched overnight.”

As it opened its first Graduate Hotels, AJ Capital was attempting to raise money for national expansion. Again, Weprin met resistance. “Try telling a foundation, pension fund, or endowment that you’re going to create a new market segment within a status quo industry that’s been the same for the past hundred years,” he says. “Good luck not getting laughed at and tossed out.”

But after opening a handful of hotels with the capital it had available, the company had proof of concept. Then, money was easier to find. In 2017, Graduate closed its first funding round of nearly $500 million. Last year, the chain opened nine hotels and raised its second $500 million.

Related: How to Set Yourself Apart From the Competition

The brand is now a national name, but even as it spreads across the country, guests often assume that their Graduate is the only one of its kind. Because unlike a DoubleTree or Days Inn, Graduate’s brand identity is too fluid to really pin down.

“Some of the big-box brands are doing school logos, mascots, or colors and then saying they’ve curated a hotel for the college experience,” says Julie Saunders, Graduate’s chief marketing officer. “But we’re staying really true to this idea of storytelling through design.”

Graduate’s design team works with notable alumni, university historians, and local artists to skin each property in a way that feels like one big inside joke with the community. In New Haven, you’ll find a pair of phone booths that call up delivery at competing pizza joints. In Nashville, you can sing a country song with a Chuck E. Cheese–style animatronic karaoke band. In Madison, you’ll find portraits of “Scanner Dan” Mathison, a local guy known for hanging around campus and chatting with students.

The shape and functionality of the hotels is also unpredictable. The 304-room hotel in Minneapolis is more than four times bigger than the 72-room hotel in Madison.

Amenities vary. So do the lobbies. In Charlottesville, the lobby resembles a college library, with a card-catalog front desk; in Fayetteville, Ark., it might as well be a bespoke hunting lodge. “It’s really not a brand,” says Weprin, by way of explanation.

Graduate’s lobby in Nashville

Image Credit: Courtesy of Graduate Hotels

“It’s a collection. But the common thread is that there’s real purpose and meaning behind every square inch.”

This kind of localizing can come with risks: There’s a difference between a school’s past and what people want to wake up to in the morning. In Ann Arbor, Mich., for instance, guests complained about photos of the Naked Mile, an annual nude run that was shut down in the early 2000s. And in Providence, they were unhappy to see portraits of Buddy Cianci, the former mayor who was jailed for racketeering. In both cases, Graduate replaced hundreds of framed art pieces in rooms with more agreeable references.

Ultimately, Graduate’s goal is to do more than reflect the community — it wants to become part of the community. To draw in current students, Graduate maintains sprawling lobbies and coffee shops with free wi-fi. (What’s a college experience without people studying, right?) And the company markets hard during orientation to lure freshmen who will spend four years growing with the brand. “If they can get students into their coffee shops and bars, and have parents stay there when they visit, then they’re creating memories that carry into the future,” says Bonnie Knutson, Ph.D., a professor of hospitality business at Michigan State University. “Then it’s the first place they’ll think of when they come back as an alumnus.”

This way, Weprin figures, Graduate can draw a lifetime’s worth of value out of each customer. They’ll return to it again and again, the way they go to Disney World and reconnect with their youth.

But that does occasionally pose a challenge — like, say, if Graduate is opening on a brand-new campus with no past to revel in. What then?

It’s the question Weprin and his team are wrestling with as they build out on Roosevelt Island. Cornell Tech is brand-new; there’s no nostalgia to beckon. And that’s not the only complication. “You can’t actually dig down, or you go through the island and into the East River,” says Rochefort. “And we have to build this in the middle of an operating campus.”

Related: Is Focusing On a Specific Niche Really That Important?

Their solution: Sidestep Cornell Tech’s historical scarcity, and focus on island lore. On the walls, you’ll see references to the old smallpox hospital and prison that used to be here. You’ll see both King Kong, who terrorized riders on the tram that goes from Manhattan to Roosevelt Island, and Nellie Bly, an investigative reporter who faked insanity to get inside the lunatic asylum. The building is modern, with floor-to-ceiling windows and an upscale rooftop cocktail bar. But in honor of the first settlers, the wallpaper in the rooms will carry a Dutch print.

It’s not exactly nostalgia, so Graduate uses the term newstalgia — and you’ll catch the vibe as soon as you approach the building. Outside, parked by the entrance, you’ll see a DeLorean, the car from Back to the Future. “We’re not chasing cool,” says Weprin.

“We’re chasing timelessness; yesterday’s past and tomorrow’s optimism.”

The Roosevelt Island project also allowed Graduate Hotels to test out a new business model. Rather than just build a hotel adjacent to a campus, this one functions as a public-private partnership. In exchange for a hundred-year lease on campus, Graduate is building and running this hotel on behalf of the university. This model, according to the company, opens up a whole new world of markets, increasing its original list of 50 target markets to 100. “We think this is the future of new campuses,” says Weprin.

“There’s no precedent for what we’re building here.” In fact, it has already replicated the deal in six other places around the country — with likely more to come.

The lobby in Eugene, Ore.

Image Credit: Courtesy of Graduate Hotels

Clearly, Graduate Hotels has a compelling idea. But what makes it a truly big idea? That has to do with timing.

The past two or three decades have seen major shifts in the hotel industry. “Back then, travelers didn’t have TripAdvisor to help them do research,” says Bjorn Hanson, Ph.D., a New York–based hotel researcher and consultant. “So they wanted that very uniform brand standard, whether they were going to Maine, California, or Hawaii.”

But the internet fragmented the market. Once customers could read reviews, examine neighborhoods on Google Maps, and tour rooms virtually before they arrived, they became more willing to try new hotels. They might want a robust gym during a two-day work trip, or a rooftop pool during a romantic getaway. As a result, hotel concepts proliferated.

By Hanson’s estimate, there are now 400 hotel brands in the U.S., and the bulk of the ones you recognize fall under one of half a dozen umbrellas. IHG runs 15, Wyndham runs 19, and Marriott has more than 30.

Customers could be forgiven for confusing Fairmont with Fairfield, or Tryp by Wyndham with Tru by Hilton. “There are so many brands,” says Fevzi Okumus, Ph.D., preeminent chair professor at the University of Central Florida’s Rosen College of Hospitality Management. “To be honest, as a professor, I have to study to differentiate how A brand is different than B brand. They’re all trying to offer the same thing, more or less.”

Related: 10 Marketing Strategies to Fuel Your Business Growth

This is what enabled Graduate’s ascent: The company saw a white space, or untapped market opportunity, that the bigger chains missed. “I think a number of the major hotel companies are surprised,” says Hanson. “Traditionally, those white spaces have been defined against price and service level — not by location and message. I don’t want to pick on any of my clients, but a few of them have launched major brands, and they would be very happy if they were growing the way Graduate is.”

It helps that Graduate owns and operates its hotels. Bigger chains, such as Hilton and Marriott, generally either franchise their hotels or outsource operations to a management company. Those models encourage uniformity, rather than bold design decisions.

To be fair, Graduate isn’t the only brand chasing campus life. A few schools, including Ohio’s Oberlin and Florida’s Rollins College, own and operate their own hotels, while Study Hotels, a Graduate competitor, offers sleek lodging off campus. But Study has just two locations. Graduate is by far the market leader — and its success is even getting professors’ attention.

Each year, Knutson, the Michigan State professor, has her senior-level brand-strategy students create a marketing plan for a real-world hotel. Last year, it was Hilton. But after Graduate dropped a hotel on the north edge of campus, she switched this year’s focus to the up-and-coming campus hotel brand.

As part of the project, students will hear from and present to Graduate executives. “The student newspapers will all pick up on it, too,” says Knutson. “It really positions them in a great way.”

And it’s a heck of a recruitment tool.

New Haven’s front desk

Image Credit: Courtesy of Graduate Hotels

Before he joined Graduate as the chief operating officer last year, Saxton Sharad was an industry consultant specializing in major markets. When he first sat down with Weprin, just over a year ago, he said, “Ben, how are we going to continue to be different as we grow? At two hotels, you can do it. At 30 hotels, it’s hard.”

As Sharad recalls, his new boss replied: “As we get bigger, we need to think smaller.”

The words resonated. “The passion in the way he said it, and his ability to really mean it, has been my motivating factor,” says Sharad.

While Graduate has grown to 2,300 administrators at the hotel level, AJ Capital’s corporate office has grown from about a dozen people to more than 140. And each new hire brings in more specialized expertise. “We have somebody who literally just picks antiques now,” says Weprin. “That’s all he does.” There’s also a Graduate librarian who fills fictional “yearbooks” with real stories to drive the creative design and food programs, along with people dedicated to sports partnerships, marketing, and branding.

“The downside is, maybe we take on too much,” says Weprin. “And I’d think that if I didn’t invest in the infrastructure. But that’s all we do. We just keep pouring resources back into the company to find the best people.”

Related: 15 Ways to Grow Your Business Fast

The think-small approach has allowed the brand, which now manages a total asset portfolio worth $2.5 billion, to enter big markets like Nashville and Seattle without sacrificing its identity. Big cities offer more stories, of course. And the local yearbooks are generally fatter. But the focus remains small. “In the cases where we go into these bigger markets, we still stay true to being university-first,” says Rochefort. “So if we were to go to L.A., we would anchor ourselves to UCLA or USC.”

But some mission drift seems inevitable — and as Graduate grows, its hyperlocal focus is starting to weaken. In Seattle, Nashville, and New York, Graduate partnered with Marc Rose and Med Abrous, hospitality pros who created successful cocktail programs…in Los Angeles. And in Nashville specifically, you’ll see references to Johnny Cash, Emmylou Harris, and other local legends who didn’t attend Vanderbilt.

“But the core DNA is the same,” says Saunders. “We’re not changing the messaging.”

When the Dallas branch opens this year, for instance, one of the stories driving the hotel restaurant will be based on a watermelon stand owned by the hotel’s previous owners. “It’s not as on the nose as other Dallas stories, but we have to make sure that it still feels distinctly Graduate,” says Sharad. “Otherwise we just become a commodity.

We become every other hotel in a big city.”

That’s how you grow big by thinking small.

A Nashville suite

Image Credit: Courtesy of Graduate Hotels

Looking forward, the company’s biggest challenge might be that it will eventually run out of universities big enough to support a neighborhood hotel. Of the original 50 markets it set out to conquer, Graduate has branches open or in progress in about half, says Rochefort. Then it will check off all the available public-private partnerships, and after that — well, what?

Related: 10 Ways for Small Businesses to Dominate Local Markets

The answer: Go global. Recently, Graduate announced its first two international hotels, in Oxford and Cambridge in the U.K. The company figures there are 10 U.K. markets that make sense, and then it will branch out further into Europe.

Just as each individual Graduate Hotel can morph to fit any college town in America, Weprin hopes he can continue reshaping the brand to find new avenues of growth. “There’s no example for what I plan for us to be in the future,” he says. “Most people are scared of change, right? Well, I’m scared of not changing. And we’re just getting started.”

loading…

This article is from Entrepreneur.com