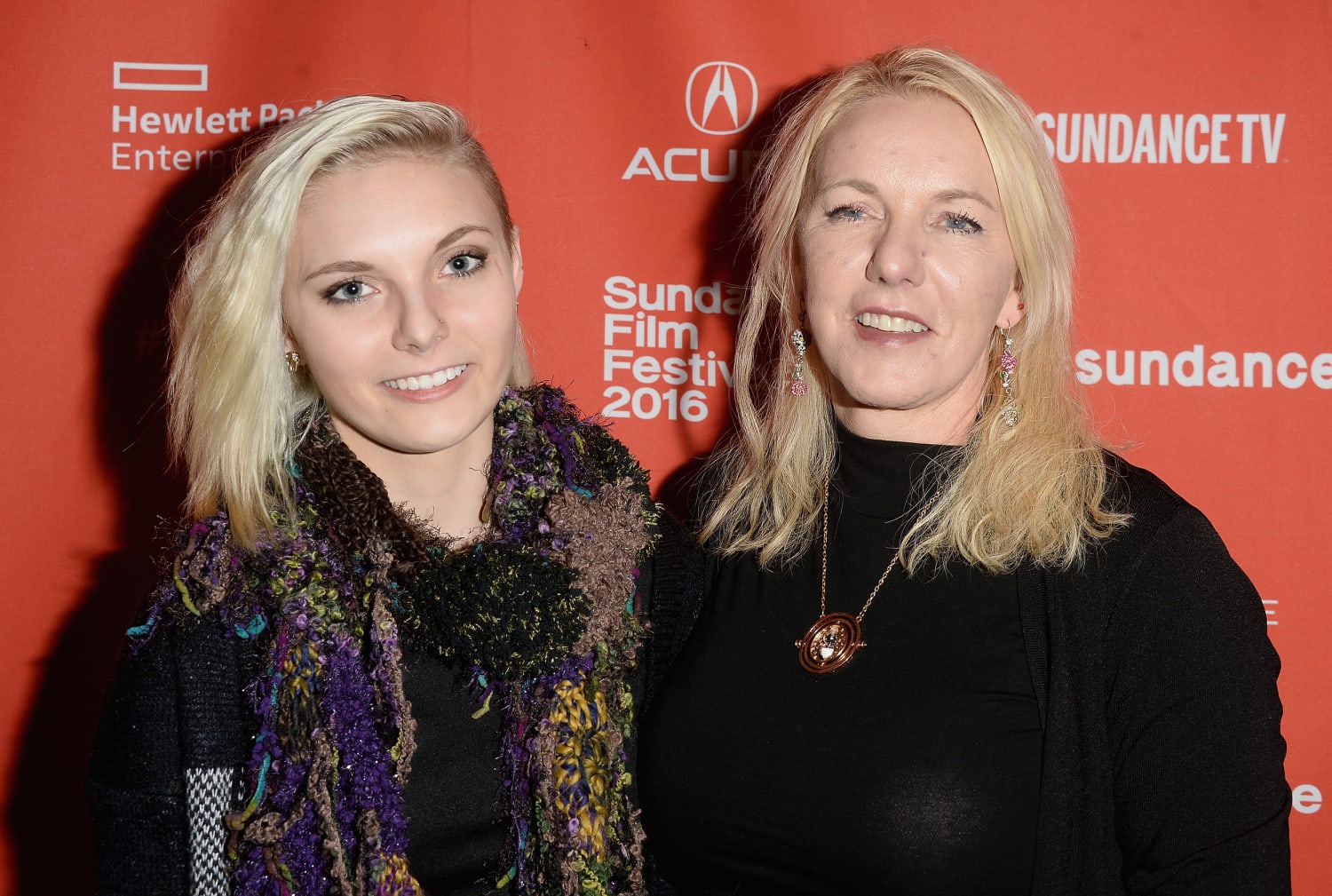

For many people, it’s a dark time right now, so we seem to be drawn to stories of how others are surviving or not. That may be one of the reasons that the painful stories of Melinda and Daisy Coleman — a mother and daughter who died by suicide within four months of each other — hold such sway.

Daisy was the subject of a documentary detailing her experiences with an alleged sexual assault when she was 14 by an older boy from a prominent family — he eventually pleaded guilty in juvenile court to endangering the welfare of a child — and with the aftermath, first in her small Missouri town and then, as her story got out, on the internet. Her mother, Melinda, lost her husband in a car accident in 2009, a son in another accident in 2018 in which she was in the car and then Daisy, all in just over a decade.

As a psychotherapist, I know that it is difficult to know what goes on in the minds of other people, even when you know them well; it is truly impossible to know what they experienced when your only information comes from the media. So what I am going to say about Melinda and Daisy Coleman is not based on knowledge of them but on my effort to imagine what might have been going on for them. In their article “Mentalization Based Treatment,” attachment theorists Anthony Bateman and Peter Fonagy call this “mentalizing,” or the process by which we humans try to “make sense of each other and ourselves.”

For a wounded, even fragile person who feels temporarily healed by positive attention, the sudden loss of that support can feel like another trauma.

The events that Daisy and Melinda Coleman experienced would be more than enough to make anyone despondent. But there might be another, less obvious reason that they were hurting (and that this story makes us sad): the pain of seeing what happens to people whose unrelated suffering becomes public — and which we ourselves consumed in the media — only for it to be forgotten when something else comes along.

Together and separately, Melinda and Daisy Coleman suffered numerous traumas before, during and after the making of Daisy’s documentary. As psychologist Ghislaine Boulanger describes in her book “Wounded by Reality,” recognition of the suffering and pain created by traumatic experiences is one of the ways survivors heal. I imagine that both mother and daughter might have felt comforted to have had their pain recognized by people outside their community — especially after having experienced harassment within it — and to be embraced by people who seemed to genuinely understand what they were going through.

But a measure of celebrity doesn’t alleviate mental health struggles; at best, it might mask them for a while. For instance, when Olivia Singh wrote about “35 celebrities who have opened up about their struggles with mental illness,” none of them suggested that their fame had helped ease the pain. In fact, in an essay for Time, Kristen Bell said about her disorder, “Anxiety and depression are impervious to accolades or achievements.”

Yet, despite knowing that celebrities suffer just like the rest of us, many of us imagine that public appreciation could make us happy.

Neither public approval nor adoption of your cause by a large group of people will bring self-esteem or self-satisfaction — let alone relief from trauma — in the long run.

As we know, though, fame and public approval are generally fleeting — those 15 metaphorical minutes are all most noncelebrities get. And in the case of people who have exposed their own deep pain and been accorded those 15 minutes because of their suffering, the subsequent fall can be excruciating.

A feeling of letdown following public admiration or recognition is normal. But for a wounded, even fragile person who feels temporarily healed by the positive attention, the sudden loss of that support can feel like another trauma. I imagine such a secondary trauma might have been part of Melinda and Daisy Coleman’s pain.

I also imagine that their pain is what again draws us to their story. We are in traumatic times, and we are looking for ways to heal. We look at their pain and wonder what will make it possible for us to bear our own.

There are ways.

In an interview on NPR, for example, the author Joan Didion described her pain and her tendency to withdraw from social contact after she lost her 39-year-old daughter and her husband within a few days of each other. But she also talked about how she used writing to process her grief.

Support groups and contact with supportive friends and family can also help. During the pandemic, numerous creative ways of making connections and staying in contact have emerged, and, even though they are not the same as being together in person, they are providing support and recognition of pain while also, in many cases, providing entertainment and distraction from the difficulties.

A measure of celebrity doesn’t alleviate mental health struggles; at best, it might mask them for a while.

When these tools are not enough, thoughts of suicide can sometimes emerge. This is a complicated, complex act, and such thoughts should not be taken lightly. If you or anyone you know is struggling with any kind of suicidal thinking, it is important to seek professional help. You can get immediate assistance by calling a suicide hotline number. (In the U.S., the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-TALK [800-273-8255] will connect you to a trained counselor.)

In an article about the mental health of survivors of Hurricane Katrina, Boulanger emphasizes that seeking help — even years after the trauma — can bring relief from the pain.

One final note: A crucial part of managing painful emotions involves a two-track approach of reality testing and distraction. Neither public approval nor adoption of your cause by a large group of people will bring self-esteem or self-satisfaction — let alone relief from trauma — in the long run.

The Colemans were clearly not able to find the help they needed when they needed it. But as we read their sad story — as we momentarily distract ourselves from our own pain — it is important to reflect on the people and activities that provide satisfaction in our lives and to focus our attention on those realities.

Source: | This article originally belongs to Nbcnews.com